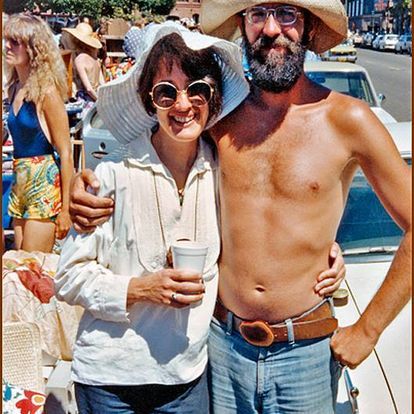

Honorably carrying the longest-lived San Francisco Street Artist Commission license #33, Dennis dedicated his mature years to photographing nature’s rhythmic, capricious, and erotic aesthetic, and the shadows and etchings left on our own life-entangled forms. While his camera wandered across the changing faces of a fading old San Francisco, he always returned to the companionship of Embarcadero and Beach St. street artist communities, the life-blood of folk art.

A navy sailor, poet, printer, and artist, a man who decried the decline of American liberalism, the decay of the infrastructure of care for each other, and the abuse of our tender planet to which we all owe our lives. We praise your ethical stand, your modest life, and the enjoyment of poetry, art, literature, light, and color that you passed to us, your sight, your gentle voice, your touch of life. May you be at peace now. Damion Dooley

CONCRETE ROOTS

by Dennis Dooley & Tom Usher

“Among large American cities west of the Mississippi, San Francisco is the only one which was not settled by the westward spread of immigrants over land. Many of its earliest inhabitants were gamblers, prostitutes, rascals and fortune seekers, who came across the Isthmus and around the Horn. The new city thus developed without Puritan influence. Not having arisen as a WASP settlement, San Francisco acquired from the beginning the mood of a large European continental city, with sections where anybody could engage in behavior of his own choice, no matter how far out. Indifference toward conventional mores and openness to cultural innovation made it a Mecca for persons in search of new life styles. And this is what the city has remained….”

—Rene Dubos,

A GOD WITHIN THE FACTS:

The roots of the San Francisco street artist movement reach into the political dynamism of the 60’s and were nurtured by the activism and love of a few individuals, some of whom are now either ignored or held in contempt by the community. It might be said that Warren Garrick and Frank Whyte, two gay artists in their forties, gave birth to the movement, even while Whyte was dying of a lung disease. Their closest ally was Bill Clark, an artist whose energy carried the movement through to its vindication by voters in the 1974 passage of Proposition J, the only successful street artist ballot initiative.

There had been efforts to sell on Haight Street in the late 60’s, and a crafts cooperative–The Quick Silver Market–was attempted in a condemned building downtown in 1970, but Beach Street in the Fisherman’s Wharf area was the real beginning, and this is where Clark met Whyte and Garrick, who was displaying sophisticated metal sculptures on the sidewalk. Beach Street, which has a magnificent view of the Bay, soon had an intimate community of 15 to 25 creative artists and musicians, and it became necessary to post look-outs for the police, who literally chased them through the streets and adjacent Aquatic Park.

The first formal organization occurred after Clark and two others were arrested on February 6, 1971. Under Garrick’s direction, the community named itself the Street Artist Guild, hired lawyers (paid partially with artworks), and devised a political strategy with which to counter the established merchants and the police.

A street philosopher tells us:”The life of the city is the life on the streets, and the businessmen and bureaucrats would like city streets to remain as sterile as the blacktop lanes that front their suburban homes. Despite the enormous pressure they bring to bear against street artists, however, the life-force is stronger, and our city experiences a renaissance of life on the streets.”

Following the loss of Aquatic Park, street artists returned to Beach Street and more police harassment. On December 4, 1971, the Guild won an injunction against arrests in Municipal Court on the grounds that, although there was a provision in the City Charter for the issuance of peddlers’ licenses, there was no regular procedure for obtaining them, and they were denied arbitrarily to street artists. Taking advantage of the now open streets and the Christmas hustle, up to 400 artists converged on Union Square. The situation became chaotic, and with the Guild and the original community outnumbered, it was impossible to maintain the formerly high quality of crafts through peer pressure. Fights broke out over spaces.

The unsavory aspects of this Union Square disorder were widely publicized as a hazard to public safety by the Ad Hoc Committee Against Street Vendors, led by Cyril Magnin. On December 21, the injunction was overruled by Superior Court, and the street artists were limited to selling at Embarcadero Plaza, which had earlier been acquired on a limited basis by Garrick through negotiations with the Park and Recreation Department. Alioto did, however, grant the Guild a short grace period to prevent mass arrests in the last few days of the holiday season.Meanwhile, Whyte became Guild secretary and corresponded with Mayor Alioto as well as then State Senator George Moscone and Assemblyman Willy Brown. Perhaps fearing bad publicity, Alioto granted a moratorium on arrests in the Spring of 1971, but quickly withdrew it when his friends in the business community threatened a law suit. Attempting to circumvent city authorities, the Guild secretly appealed to the State, and in the summer of 1971, Aquatic Park was given to them on a trial basis for 8 weekends. The number of sellers had grown to over 100 somewhat anarchistic individuals, not all of whom identified with the Guild, and the park was taken away after only two weekends due to intense opposition from business interests.

“Do not ask street artists for the time, because they have shed their watches with their last job. These neo-primitives tell time by the angle of the sun, and the length of shadows on the sidewalk. They are as sensitive as farmers to the weather, for their fortunes rise and fall with the sun and rain. They complain about harsh conditions on the street, yet immersion in the bayside’s natural elements and rhythms has left them resilient and resistant to disease. Most would find it impossible to spend their days within the immaculately controlled atmosphere of San Francisco’s proliferating skyscrapers, the windows of which cannot even be opened.”

Embarcadero was of doubtful legality and what the Guild really wanted was street spaces. In a stormy Board hearing over this issue on August 10, 1972, Clark and Garrick were arrested for disorderly conduct on the orders of Supervisor Terry Francois. Clark clung to the speakers’ podium before being dragged away by police, and soon after he resigned from the screening committee.

“These craftspeople have found what most people in our society have lost, a sense of community. Their instinct to do handcrafting led them, like Moses leading the faithful, out of the monoculture. The ecological principle of the climax state, in which a community, whether of plants, animals, or humans is healthy to the degree that it is diverse and balanced, applies to street artists. Gays mix with straights, elderly with young, educated with unschooled, and the diversity of ethnic backgrounds facilitates a rich exchange of information and warmth of human contact, which is also passed on to their customers, who do not experience anything like it elsewhere in the city.”

After unsuccessfully approaching the Board nine times in 1972 and ’73 with reasonable requests for street selling spaces, the Guild decided to circumvent the established business interests and their political allies through the initiative procedure. Clark researched initiatives and composed a Proposition, which qualified for the ballot when seven members of the Guild and a few volunteers got 26,000 signatures, and on June 4, 1974, Proposition J passed, opening the city once again to street artists. Although J was purposely drawn up to establish an orderly program–the guild was always aware that their strength lay in a good public image–various city authorities, either in collusion with business interests or out of a desire to avoid extra work, refused to implement the proposition, and another chaotic Christmas at Union Square followed in 1974. Captain Jeremy Taylor of the Police department even went so far as to say that his department would do nothing to enforce the new law.

“Through the windows of their buildings and expensive cars, most merchants, police and politicians see street artists as little more respectable than the many criminals, crazies and alcoholic derelicts who inhabit the Tenderloin and South-Of-Market areas. In fact, there is a relationship. Most street artists, who have no door with which to shut anyone out, will listen with compassion to the sad tales and often incoherent ramblings of these unfortunates.”

The chaos resulting from the City’s “do nothing” attitude brought on a calculated repression in the form of the Kopp Ordinance, a restrictive measure passed by the Board of supervisors in violation of the State Election Code, which specifies that ballot initiatives take precedence over laws passed by legislatures. 98% of the selling spaces that the voters had mandated for street artists were eliminated by the Supervisors’ action.Clark, who had been arrested 13 times for illegal street selling, quit the Guild because he disagreed with the strategy the majority was urging to fight a new proposition (L) introduced by bitterly antagonistic Supervisor Francois; the Proposition called for the repeal of J and gave the Board complete discretion over when, where and how street artists may sell their goods.

Clark would have preferred to challenge the legality of the Kopp ordinance in court, rather than following the Guild’s strategy of giving the voters an alternative to vote for on the same ballot as L. Their proposition (M), though calling for reasonable controls, would have insured by law the basic right of street artists to make a living. M lost in November, 1975, and the Guild soon withered away after its new leadership made an unpopular attempt to affiliate with established trade unions.

“Ask street artists what they like most about their street life, and they will say being their own boss, and being able to structure their own time. Ask what they like least, and they will say the financial insecurity. Established merchants propagandize that street artists make fabulous money; the truth is, they work long hours for little or moderate income, but prefer their independence to the security corporations offer their employees.”

When Jefferson Street, a magnet for profitable but tawdry enterprises in the Wharf Area, and one of the few viable selling spaces left for street artists in the city, was about to be taken away due to construction of yet another Cannery-like shopping complex, Michael Tuggeman, an enterprising bead merchant with long experience on the streets of New York, stepped into the leadership vacuum. Under his leadership, the Association hired the prominent attorney Ephraim Margolin, who preserved the Jefferson selling area for eighteen months during construction of the shopping center while defending the Associations interests on two issues: he prevented the imposition of craft quality control, which could have threatened bead craft, and, in view of the crowded selling conditions, he forestalled issuance of street artist licenses to new people.

Some older Guild members feel that these Association policies are strategically unsound insofar as they create a negative image. The Association also seeks to prevent interference by the Art Commission in a lottery originated by street artists themselves to insure equitable distribution of spaces.

“The issue of crafts quality, once an important factor, is no longer as significant in the street artist movement. Work of one’s own hands, whether stringing beads or cutting stained glass, is the accepted standard. The brilliant and those without much talent have learned to accept, and even love one another. Despite their many differences, including the quality of their products, street artists seem to have one aspect in common–they dislike unnecessary authoritarian policing of what they make, and how they sell it.”

Current prospects have been colored by the assassinations of Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Milk. Ironically, the new Board of Supervisors might be more liberal and favorable to street artists. Terry Francois is too busy with his fried chicken concession at Pier 39 to harass street artists, and Dan White, whose hot potato stand is directly across from Francois’ Chicken, cannot do much from his jail cell. On the other hand Mayor Feinstein, characterized by her daughter as “efficient and compulsive,” has long wanted artists off the streets, and will probably seek their removal into enclosed areas.

The Association is bargaining for spaces at the airport, and for enclosed selling malls in the Wharf area, but in locations more desirable than Feinstein would choose. Howard Lazar of the Art Commission sees the street artists amid a sylvan setting in the redeveloped waterfront. Many street artists feel that it is essential to retain whatever foothold they have left on the streets, which symbolize their freedom and their lifestyle, no matter how attractive the alternatives that may be offered. Lazar has received many inquiries about the program from other cities, and he claims that “for the last seven years, the eyes of the nation have been focused on the San Francisco street artists.

“Saturday morning. A chill fog envelops Aquatic Park as the first Street Artists arrive on the green to have their license numbers written on slips of paper, which are dropped into a revolving drum. With far too few selling spaces for the number of artists, each hopes for luck, and astrological calculations, a wisdom source for some, are discussed. Dogs and children scurry about, as close to three hundred people gather on concrete bleachers facing the water. The buzz of money talk, a major preoccupation in every market place, subsides as their consensus leader, a short, balding Jewish man raises a bullhorn and implores them to attend an important supervisors’ meeting and to contribute money for legal funds. A collection is taken for a street artist injured in an auto accident.

As the drawing of numbers is announced, a large man rushes through the crowd, imploring the lottery helpers to wait until he enters his number. He has come a long way, is one of the original street artists, and though he is late, the rules have been bent before. Not this time, he is told. Enraged, he lifts the drum, runs to the water, and heaves it far out into the waves–lottery numbers fly in all directions. After a few silent seconds, three hundred people laugh uproariously. He is one of their own.